About Ticks

Ticks are an indisputably dreaded enemy. Ticks are external parasites that feed on the blood of their hosts. They are attracted to warmth and motion, often seeking out mammals – including dogs. Ticks don’t fly, jump o r blow around with the wind, they are slow and lumbering. Ticks tend to hide out in tall grass or plants in wooded areas waiting for prospective hosts. Once a host is found, the tick climbs on and attaches its mouth parts into the skin, beginning the blood meal. Once locked in place, the tick will not detach until its meal is complete. It may continue to feed for several hours to days, depending on the type of tick. On dogs, ticks often attach themselves in crevices and/or areas with little to no hair – typically in and around the ears, the areas where the insides of the legs meet the body, between the toes, and within skin folds.

r blow around with the wind, they are slow and lumbering. Ticks tend to hide out in tall grass or plants in wooded areas waiting for prospective hosts. Once a host is found, the tick climbs on and attaches its mouth parts into the skin, beginning the blood meal. Once locked in place, the tick will not detach until its meal is complete. It may continue to feed for several hours to days, depending on the type of tick. On dogs, ticks often attach themselves in crevices and/or areas with little to no hair – typically in and around the ears, the areas where the insides of the legs meet the body, between the toes, and within skin folds.

Ticks Are Experts at Finding Hosts

Ticks are very patient and amazing in their capacity to locate their host/prey. They sense motion, body heat and carbon dioxide (which is exhaled by mammals). They have a sticky substance on their bodies that enables them to easily cling to the fur of passing animals such as your dog. They then crawl down the hair to the skin and latch on, taking a big bite to attach its mouth parts. The tick drinks the host’s blood until it becomes engorged.

Their purpose in life is only to propagate their species and unknowingly pass diseases to those hosts they feed on. They don’t feed often, but  when they do, they can acquire disease agents from one host and pass it to another host at a later feeding. Their sensory organs are complex and they can determine trace amounts of gases, such as carbon dioxide left by warm-blooded animals and man. They can sense the potential host’s presence from long distances and even select their ambush site based upon their ability to identify paths that are well traveled.

when they do, they can acquire disease agents from one host and pass it to another host at a later feeding. Their sensory organs are complex and they can determine trace amounts of gases, such as carbon dioxide left by warm-blooded animals and man. They can sense the potential host’s presence from long distances and even select their ambush site based upon their ability to identify paths that are well traveled.

The Dangers of Ticks

Though they are known vectors of disease, not all ticks transmit disease – in fact, many ticks do not even carry diseases. However, the threat of disease is always present where ticks are concerned, and these risks should always be taken seriously. Most tick-borne diseases will take several hours to transmit to a host, so the sooner a tick is located and removed, the lower the risk of disease. Many of these tick-borne diseases are contagious to people as well as our pets. Their efficiency at spreading infection comes from the way they feed. Many tick species feed on at least three hosts before they die. The tick’s saliva travels into the wound to keep the blood from clotting. The saliva carries infectious material into the wound. If squeezed during grooming or during an attempt to remove it, the tick may regurgitate infected blood back into the wound. If one host is sick, the tick can carry the infection to the others. Hard ticks also have to keep their mouth parts embedded in their hosts’ skin for hours or even days before they finish a meal. This gives pathogens plenty of time to make their way into the host.

The symptoms of most tick-borne diseases include fever and lethargy, though some can also cause weakness, lameness, joint swelling and/or anemia. Signs may take days, weeks or months to appear. Some ticks can cause a temporary condition called “tick paralysis,” which is manifested by a gradual onset of difficulty walking that may develop into paralysis. These signs typically begin to resolve after tick is removed. If you notice these or any other signs of illness in your dog, contact your veterinarian as soon as possible so that proper testing and necessary treatments can begin. The following are some of the most common tick-borne diseases:

- Lyme disease

- Ehrlichiosis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Anaplasmosis

- Babesiosis

- Anemia

The diseases ticks transmit vary from place to place. This is because different animals and their species-specific diseases thrive in different parts of the world. But that doesn’t stop tick-borne illnesses from spreading outside of a particular geographical area. Many rickettsia (highly pleomorphic bacteria) illnesses are spotted fevers that cause rashes, nausea, vomiting, headache and fatigue. Most of the time, these illnesses respond to antibiotics, but some can be fatal without prompt medical treatment. Black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks, can carry a bacterial infection called Lyme disease. Lyme disease exists in Europe, Africa, Asia and much of the United States. It causes a red bull’s-eye rash, fever, headache, a stiff neck and muscle pain. Ticks can also transmit the malaria like illness babesiosis (caused by microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells and are spread by certain ticks), which comes from protozoa (one-celled organisms (called protists) that live in water or as parasites). Some tick-borne illnesses are dangerous only to animals, such as swine fever, which infects pigs, and canine prioplasmosis, which infects dogs.

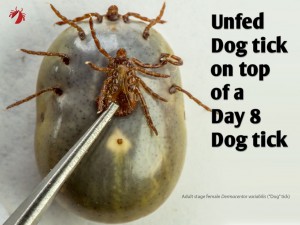

Tick Anatomy

Many people group ticks into the same category as fleas and mosquitoes — insects that suck blood. However, ticks are really arachnids. Adult insects have three pairs of legs, and their bodies are made up of three segments: the head, the thorax and the abdomen. Arachnids, on the other hand, have four pairs of legs. Spiders are also arachnids, but ticks aren’t spiders. Spiders’ bodies have two segments, the cephalothorax (the head and thorax is fused) and the abdomen, while ticks’ bodies aren’t segmented in any way. A tick’s body is small and relatively flat, so it’s easy for it to attach itself to a host and eat its fill before the host notices. This is particularly true for immature ticks, which can be smaller than the period at the end of a sentence. Hungry adult ticks are often smaller than sesame seeds. Many ticks have to stay in place for a day or more to finish a meal, so the ability to go unnoticed is central to its survival.

Adult ticks have eight legs, each of which is covered in short, spiny hairs and has a tiny claw at the end. These spines and claws have two main purposes. They help ticks grasp blades of grass, leaves, branches and other vegetation. They also allow ticks to grasp their hosts.

Ticks use their mouthparts to pierce their hosts’ skin and extract blood. These mouth parts can vary from species to species, but in general, from the outside to the inside, a tick’s mouth includes:

Ticks use their mouthparts to pierce their hosts’ skin and extract blood. These mouth parts can vary from species to species, but in general, from the outside to the inside, a tick’s mouth includes:

- Two palps, which move out of the way during feeding and don’t pierce the host’s skin

- Two chelicerae, which cut through the host’s skin

- One barbed, needle like hypostome

Hard and soft ticks both have these mouthparts, although you can only see them on a soft tick if you look at its underside. At its most basic, a tick is a parasitic blood pump. Like all parasites, it feeds off of its host without giving the host anything in return. A tick’s body has numerous adaptations that allow it to find hosts and ingest their blood.

The barbs on the hypostome are like the barbs on a fishhook. They point back toward the tick, making it difficult to remove the tick without damaging the skin. Some ticks secrete a cement like substance with their saliva, which dissolves when the tick is ready to drop off of its host. This substance can make it even harder to remove the feeding tick. The saliva also keeps the host’s blood from clotting while the tick eats. But unlike a flea’s saliva, it doesn’t usually include compounds that cause itching and swelling.

As a tick eats, its body expands, although the amount of expansion varies. The Scutum of a male hard tick covers much of its back, so its body can’t stretch to hold a lot of blood. Soft ticks don’t have a Scutum to get in the way of feeding, but they don’t require an immense store of blood to lay eggs, so they don’t swell as much as hard ticks do. Female hard ticks swell immensely as they store the blood they need to lay their eggs.

Ticks themselves are just as diverse as the diseases they carry. They live all over the world, and there are as many as 850 total species, divided roughly into two categories — hard and soft. A hard tick has a shield-like plate called a scutum that covers part of its back. If you look at a hard tick from top down, you can also see its capitulum, which looks like a head. Soft ticks, on the other hand, don’t have a scutum, and the only parts of it you can see when you look at it from above are its back and legs.

Regardless of whether they’re hard or soft, all species of ticks have a few things in common. Everything about them, from their swollen appearance to their ability to spread disease, comes from their need for blood.

Most species of ticks go through four life stages – eggs, larvae, nymphs, and adults.  All stages beyond eggs will attach to a host for a blood meal (and must do so in order to mature). Depending on species, the life span of a tick can be several months to years, and female adults can lay hundreds to thousands of eggs at a time.

All stages beyond eggs will attach to a host for a blood meal (and must do so in order to mature). Depending on species, the life span of a tick can be several months to years, and female adults can lay hundreds to thousands of eggs at a time.

Ticks can also starve to death, but often the process takes months or even years. However, without food, ticks can’t do much. Ticks are a clear illustration of how food works as an energy source. Ticks need energy from blood in order to grow, develop and lay eggs. Without blood, ticks can’t do any of this.

A tick begins its life as an egg. When the egg hatches, a six-legged larva emerges. Aside from its missing set of legs, the larva looks a lot like an adult tick. Its first host is usually a small mammal or a lizard, and it has to find a host in order to grow. After feeding, the larva drops to the ground to digest its food and begin to grow. After one to three weeks, the larva molts and becomes a nymph.

A tick begins its life as an egg. When the egg hatches, a six-legged larva emerges. Aside from its missing set of legs, the larva looks a lot like an adult tick. Its first host is usually a small mammal or a lizard, and it has to find a host in order to grow. After feeding, the larva drops to the ground to digest its food and begin to grow. After one to three weeks, the larva molts and becomes a nymph.

A tick nymph has eight legs and looks like a smaller version of an adult tick. It has to find another meal, usually from another small mammal, bird or lizard, before it can molt again. Once the nymph is finished eating, it drops to the ground to continue its development. Some species of soft tick molt several times, consuming a blood meal before each molt. After its final molt, the tick is an adult.

An adult tick has one job — to reproduce. In hard ticks, the female tick attaches to a host and feeds, often for more than 24 hours, before mating. The male tick feeds before mating as well, but he’s often a fraction of the size of the engorged female when mating takes place. Often, the male dies after mating, and the female dies after laying anywhere from 2,000 to 18,000 eggs. Soft ticks are an exception. Many species of soft ticks eat several smaller blood meals and lay eggs several times.

Tick Behaviour

Hard and soft ticks differ in how they behave and find food. Soft ticks generally live in animals’ nests and burrows. Females lay their eggs in their host’s nest. Larvae, nymphs and adults crawl through the nest to find hosts. They usually feed at night, and they don’t spend much time attached to a host. While hard ticks may spend days consuming a host’s blood, soft ticks often finish a meal in about the time it takes a flea to do the same task.

Hard ticks, on the other hand, find food through a behaviour known as questing. A questing tick positions itself on a blade of grass, a leaf or other vegetation. It stretches its clawed limbs outward and waits for hosts to pass by. Ticks can’t jump or drop down onto their hosts — when a host brushes against a questing tick, the tick simply hangs on. In many tick species, larvae quest at ground level. Nymphs climb a little higher into vegetation to find slightly bigger hosts. Adults climb highest of all in their attempt to find large animals to use as hosts.

Questing often involves a lot of waiting, and it may seem like such a haphazard method wouldn’t be very successful. But ticks use several signals to decide when and where to quest. Many tick species have eyes and can detect colour and movement. Hard and soft ticks can detect carbon dioxide (CO2) that animals produce as they exhale. By following these signs, ticks have a good chance of finding hosts.

Some species of hard ticks don’t spend much time questing. They find a host as larvae and stay on that host for their whole lives. These are known as one-host ticks. A few species are two-host ticks. They mature from larvae to nymphs on one host, then find a second, larger host as adults. Most hard tick species are three-host ticks, which feed and drop to the ground at each stage of their lives.

Controlling Ticks in Your Home and Yard

Ticks like to live in overgrown weeds, leaf litter and decaying wood, so it’s good to clean up any such areas in your yard. They tend to hide out in tall grass or plants until a host is found. Though there are plenty of ticks in wooded areas, this is not their only habitat. Ticks can live in your backyard. Keeping grass short and plants neatly pruned can help minimize the presence of ticks, but there is no guarantee. Sadly, ticks don’t take vacations. Your pet can get bit by a tick year round.Check your dog regularly for ticks as a precaution. Also remember that some ticks may hitch a ride into your home on the dog, then jump onto you or another pet.

The best way to protect your dog from ticks is to prevent them in the first place. There are a variety of tick prevention products that can help keep your dog safe (some also prevent fleas). However, none are 100% effective. If you live in an area where ticks are prevalent (cows, horses and birds), you should check your dog on a regular basis. Removing ticks before they attach (or shortly after) will help prevent disease. Remove the tick by firmly grasping it (use a pair of tweezers) close to where it is attached to your pet’s skin and applying backwards pressure. Kill the tick by placing it in a small container of alcohol or dish washing liquid.

Preventing Ticks on Your Pets

It’s important to use a tick preventive product on your dog. A pesticide product that kills ticks is known as an acaricide. Acaricides that can be used on dogs include dusts, impregnated collars, sprays, or topical treatments. Some acaricides kill the tick on contact. Others may be absorbed into the bloodstream of a dog and kill ticks that attach and feed.

Topically applied products:

- Fipronil

- Pyrethroids (permethrin, etc.)

- Amitraz (Tactic)

- Bayticol

Getting rid of ticks can take a little persistence. If commercial tick-control products don’t do the trick, contact your local exterminator for assistance.